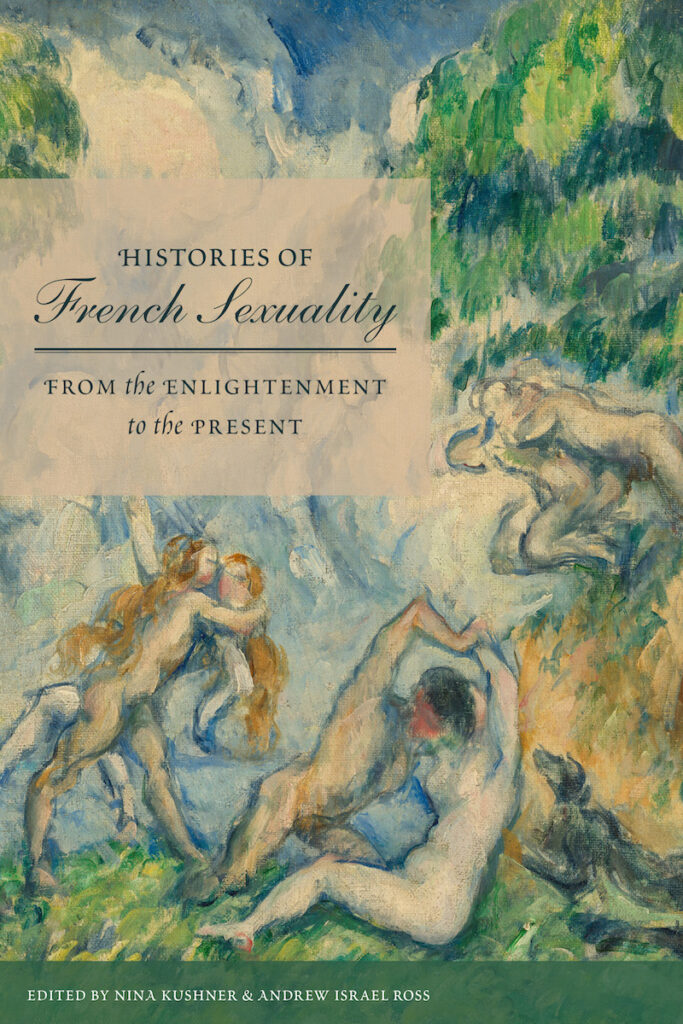

It has been a long while since I’ve lasted posted, but I am excited to do so to announce my new book, an edited collection completed with Nina Kushner (Clark University), titled Histories of French Sexuality: Enlightenment to the Present. Chapters cover a wide range of thematic, temporal, and geographic ground all in the service of showing how centering sexuality might change our understanding of French history.

From the publisher:

Histories of French Sexuality contends that the history of sexuality is at a crossroads. Decades of scholarship have shown that sexuality is implicated in a wide range of topics, such as studies of reproduction, the body, sexual knowledge, gender identity, marriage, and sexual citizenship. These studies have broadened historical narratives and interpretations of areas such as urbanization, the family, work, class, empire, the military and war, and the nation. Yet while the field has evolved, not everyone has caught on, especially scholars of French history.

Covering the early eighteenth century through the present, the essays in Histories of French Sexuality show how attention to the history of sexuality deepens, changes, challenges, supports, or otherwise complicates the major narratives of French history. This volume makes a set of historical arguments about the nature of the past and a larger historiographical claim about the value and place of the field of the history of sexuality within the broader discipline of history. The topics include early empire-building, religion, the Enlightenment, feminism, socialism, formation of the modern self, medicine, urbanization, decolonization, the social world of postwar France, and the rise of modern and social media.

Order now using code 6AS23 for a 40% discount from University of Nebraska Press!