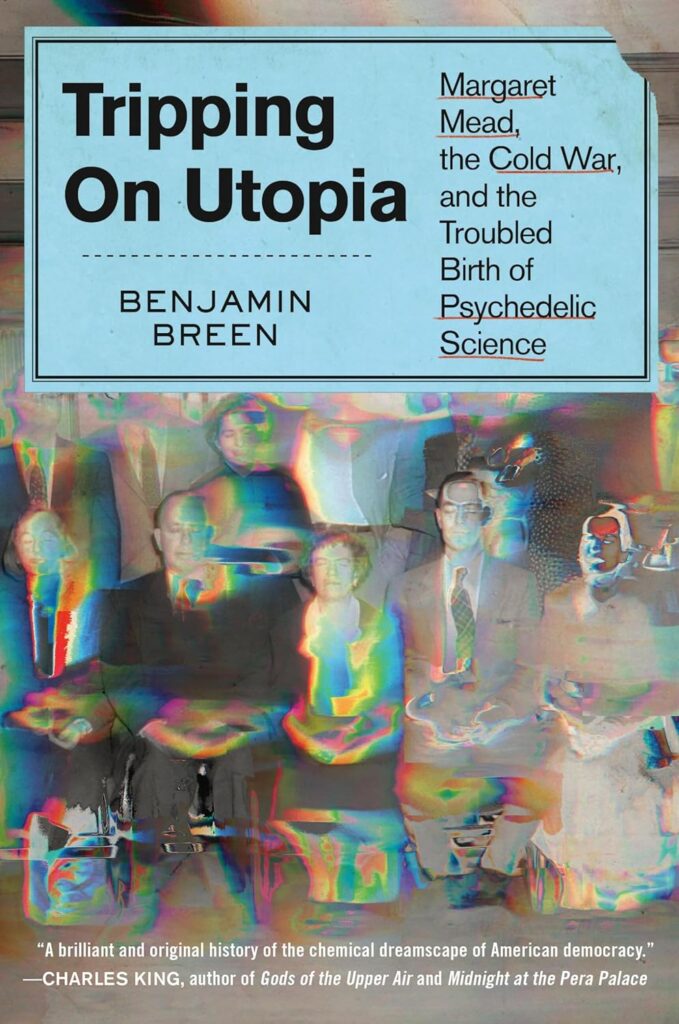

I just finished reading Benjamin Breen’s Tripping on Utopia for my book club. This was one of those nice instances where I got to read some history for pleasure. The book was pretty much perfect for this kind of exercise. Breen is an excellent narrator and he makes the story truly compelling even as it goes into a great deal of detail and includes a dizzying array of people who were involved in psychedelic research around Margaret Mead’s circle. The book argues that Margaret Mead and many of those around here — notably her one-time husband Gregory Bateson — saw psychedelics as one path toward a new world order based on expanding human consciousness so to bring the world closer together. They meant this both as an ideology — respect and appreciation for cultural difference was at the center of their belief system — and as practice — they once argued for a world government in order to do away with nationalism (72-79). Mead rested these hopes, Breen argues, on a faith in science.

The idea of science works in two registers in the book, neither of which quite worked for me, and left me with some remaining questions. In the first, Breen describes Mead’s own view: “science as a cross-cultural utopian project” (279). In the second, Breen describes Mead herself as a scientist. From the same page: “Margaret Mead had numbered among the planet’s most celebrated scientists.” Margaret Mead, however, was an anthropologist. Many of the people around her were psychologists. The experiments with psychedelics that many of them participated not only, as Breen acknowledges, hugely problematic in terms of consent, but also in terms of methodology. In what way were these people scientists and in what way was what they were doing science?

I am not a historian or philosopher of science, so I don’t really know the answer. But I wish the book had gone a bit further into questioning these assertions. Mead, it seems to me, was asserting herself as a scientist (rather than a social scientist) in order to rest her claims on a more object or concrete version of truth than she could otherwise. But the fact remains that her method was not the same as someone working in, say, biology of physics. Her claims about other cultures were based, not on the kind of experimentation necessary to those fields, but of ethnography and observation, necessarily subjective and reliant on the relationship between observer and observed. Likewise, very few, if any, of the experiments using LSD described in the book would pass muster as science as far as I could tell.

Deploying a more skeptical framework might have enabled the book to show what I think is implicit here. That these utopians were basing their hopes for the future on knowledge that in fact could not simply be gained by science. That there remains important work to do not only in anthropology, but also I religious studies, history, political science, literature, and other fields in the humanities and social sciences that cannot rest on the kinds of certainties required of modern drug research. And moreover that these fields might be broadly applicable to the world in which we live. That, having read Breen’s book, is my conclusion about Mead: she sought to take her awareness and love of diversity and apply it in ways that might have made the world a better place. Science isn’t the only avenue for accomplishing this task.

One thought on “The Science of Utopia?”