About a week ago, just as the protests and uprisings against police brutality began in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, a woman named Amy Cooper called the police after being asked to put her dog on a leash by a Black birdwatcher named Christian Cooper (no relation) in Central Park. Prior to calling, Amy Cooper warned that she was “going to tell them [the police] there’s an African American man threatening my life.” As many others have noted, in doing so, Cooper deployed her white privilege to threaten the possibility of state violence in ways that resonated with the long history of white women pointing fingers at Black men who were then subjected to extrajudicial violence. The most famous case, of course, was the lynching of Emmett Till who was murdered in 1955 after a white woman named Carolyn Bryant claimed that he had whistled at her. Bryant recanted in 2017.

I started thinking about this moment again as I continue to work through Josephine Butler’s Government by Police (1879). Butler connects the growth of police power in both Continental Europe and in the United Kingdom to the growth of moral policing, especially around the development of regulated prostitution. For Butler, then, the police posed both a general danger to liberal society and a particular danger to women. Butler’s feminism — at first — was thus organized around protecting women from the police, not calling on them in women’s defense.

Thinking on this fact in light of recent events returned me to a theme I address toward the end of my book, which shows how middle-class Parisians began to call on the police to harass and arrest female prostitutes (among others) that they encountered on the streets. For Butler, as I said yesterday, the Paris Prefecture of Police and specifically its morals brigade served as her primary example of the dangers of police power. Butler went to Paris several times during the 1870s, when the relationship between the police and the people was very much in flux. Ostensibly a Republic, the police remained largely holdovers of the authoritarian Second Empire. It remained somewhat unclear whether the police existed to exercise power over the people or in the name of the people. One way for citizens to make claims for the latter was to write to the police and demand they act in their interests, which thousands of Parisians did over the course of the following decades.

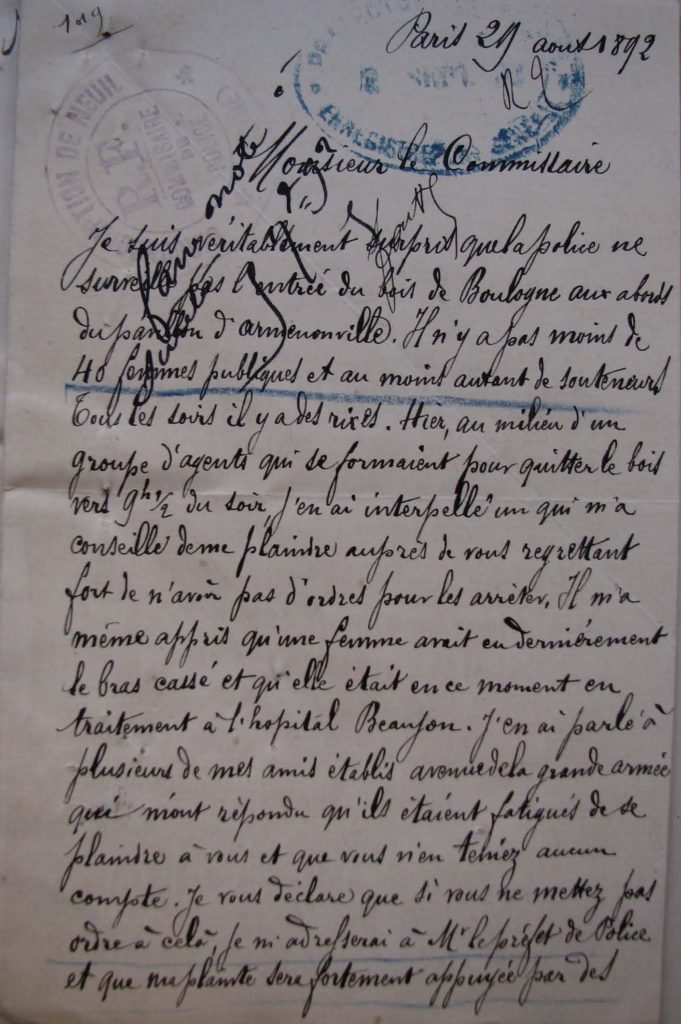

I document numerous examples in the book, but here’s just one that might resonate a bit more than others with the Cooper case. In 1892, a man who signed his letter B. Rousseau called on the police to clear out the prostitutes and pimps who hung around the entrance to the bois de Boulogne (the large park on the western side of Paris) (see the image above). If the police ignored his request, Rousseau warns, he would write directly to the prefect and the newspapers. He asked, finally, “Where is our money going, if we are ourselves reduced to playing police?” (166). Rousseau’s letter speaks to his confidence that the police will act to clear the park of those he deems undesirable because he, after all, pays his taxes which in turn pays the police. The police, as with Amy Cooper, were called to determine who had the right to use a public park and how that space could be used.

However, Rousseau’s call on the police was precisely to prevent women from using public space, not to preserve their right to it. It is worth remembering how recently young women in Central Park would have been seen as disreputable at best. Indeed, how do we know the women Rousseau declaimed actually were prostitutes? We don’t. And thus we are confirmed in Butler’s critique that by endowing the police with such authority over working-class women, they threaten all women. There has been a good deal of justified talk recently. about the ways that white people, and white women in particular, threaten the lives of Black people. It might be worth thinking back to these early moments to recognize the ways that white women too were once threatened by the police. In doing so, we might be able to reinvigorate connections that have otherwise been lost as white women deployed their political power to serve their racial interests.

Butler’s own path serves as a warning to failing to remember these early conflicts between women and the police. Butler successfully convinced Parliament to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts in 1886 (she had less success on the Continent), her commitment to reducing police power waned. As she and many other late nineteenth-century feminists turned increasingly to the question of “white slavery” they became much more willing to utilize and deploy state authorities to their own ends. Put differently, once the specific threat of police power receded, these activists were willing to try to deploy it in new ways. This strategy backfired, as Judith Walkowitz has argued, with the police increasingly able and willing to use their power to repress sexual diversity and feminists ultimately losing control of their own movement. You may think that the police are there to act in your interests; you may find out that the opposite is much more likely to be the case.

Through social media, I’ve seen some signs at protests arguing in effect that the police work for us, not the other way around. But I’m increasingly unsure if that was ever the case or ever really possible. At the very least, the “us” never seems to include the people at most risk of victimization. And it’s quite possible, it seems, that it never will.