Even before the pandemic, I had been moving most of my examinations away from traditional in-class exams and toward a take-home format. This was mostly because it felt like a contradiction to try to teach students that history was not about the memorization of dates and then have them complete a timed exam for which memorization was a large component. In the wake of the pandemic, a take-home exam also felt more accessible: students could complete it at their own pace, focus on what they felt most comfortable, and use their own notes and the course materials at home. As of last semester, I was even having students brainstorm questions they would like to appear on the exam so that it could play to their strengths and encourage them to really think about what they learned in preparation for the exam.

This move had pluses and minuses. It certainly did decrease student anxiety about memorization. It also provided flexibility during the exam period. It allowed students to take a bit more control over their own learning at the end of the semester. However, especially in introductory courses, there were significant downsides. It was difficult to develop questions sufficiently tailored to the course to prevent cheating. Many responses did not show the kind of deep thinking I thought a take-home option would enable. Despite having access to all the information from the course (and the internet) answers remained superficial, without a great deal of detail in their argument or evidence.

These issues only became more severe this semester, in the middle of which ChatGPT and similar AI Chatbots dropped. I had, for most of the semester, taken a rather laissez-faire attitude to these tools, thinking that some students will inevitably cheat, but that its a minority group. However, what seems to have happened with my final is that rather than simply using ChatGPT to write an answer, a significant number of my students typed in the prompt, looked at the answer provided, and then wrote their own response around it. I have no proof of this and decided, after some thought, to not pursue it with the students.

Students in my HS 100 course developed a question about the origins of the French Revolution, especially insofar as it involved the Third Estate. I knew that this question was probably all over the internet, but not wanting to change my course policies entirely (I did write one of the questions that appeared on the exam myself, without their input), I put the question on the exam. It read:

France faced a number of problems prior to the French Revolution, but perhaps none were more important than those that affected members of the “Third Estate.” In a short essay, identify at least two problems facing the Third Estate, explain why they were problems, and describe how they contributed to the outbreak of the French Revolution. In answering, be sure to make explicit reference to at least two primary sources we read in class.

If you Google something like “origins of the French Revolution Third Estate,” one of the first hits is “AlphaHistory,” a kind of SparkNotes for history that I sometimes see appear on student work (cited and not). It describes some of the issues facing the Third Estate, including its huge diversity, the peasantry, urban workers, etc. In fact, this isn’t a bad description and follows pretty closely the text we read in class about this issue, the entry on the Social Origins of the French Revolution from Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. Both sources describe some of the ways inequality and hierarchy differently affected members of the Third Estate.

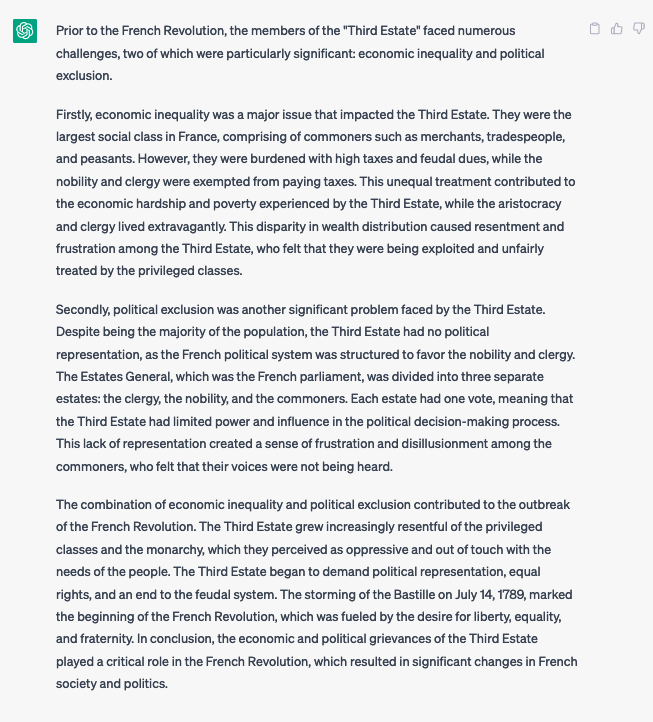

If you simply copy and paste my prompt, without the last sentence, into ChatGPT (or Google’s Bard, which is what I initially used to test this out), you get what I see as a simpler answer to the question:

About half of the class chose this question to answer and a little over half of that number gave the same answer: the Third Estate faced two problems, economic inequality and political exclusion. Indeed, they used those exact words. My sample size was small (about four students out of six who answered the question gave this answer, out of 12 students in the class), but I am suddenly very concerned about the use of generative AI in my classes.

This essay in The Atlantic gets at part of why this is so disappointing. At least when using standard search, students would have to sift through multiple possibilities, assessing what to use and what not to use. One webpage might emphasize the various classes that constituted the Third Estate, while another might discuss in more general terms the macro reasons for their discontent. It remained up to the student to decide which was more convincing. In addition, students would see hyperlinks taking you to other sources; some may even contain references to primary and secondary sources. ChatGPT just tells you the answer, which it declares to be “general knowledge” (even when it is wrong about one of the most important events in French History):

This takes all the thinking out of the equation, which is precisely what we’re supposed to be teaching.

I’m still ruminating on the solution to the problem, which is not just the cheating, but also the fact that this kind of tool seems — to students — to eliminate the need for the basic starting point of any form of critical thought: the need to consider, for oneself, what is being asked and the various ways one might answer.

For now, I certainly won’t be offering a take-home exam any longer and will probably replace it with an in-class, open-note exam since I remain convinced that it is important for students to work on answering broad questions about course content. They need to exercise that part of the brain. The bigger question might be about what to do about the ways ChatGPT can be used to circumvent brainstorming and the production of an initial idea. It is that problem that I’ll be using the summer to consider how to address next semester.