In the wake of rising Covid-19 cases, Baltimore City has once again closed indoor dining and bars. I feel terrible about how this act might affect those in the service industry, but ultimately it seems like it was inevitable considering the failure of the federal government to act and the impulse among individual states to reopen well before caseloads had declined to the extent they have in other places in the world. While they may be open again by the time the semester starts, I’m also thankful because it means that students won’t be congregating in bars around the city.

Continue reading “Let Students Drink”Blog

Scenes from Baltimore

Some pictures from today’s big protest in Baltimore (a local news report and aerial views).

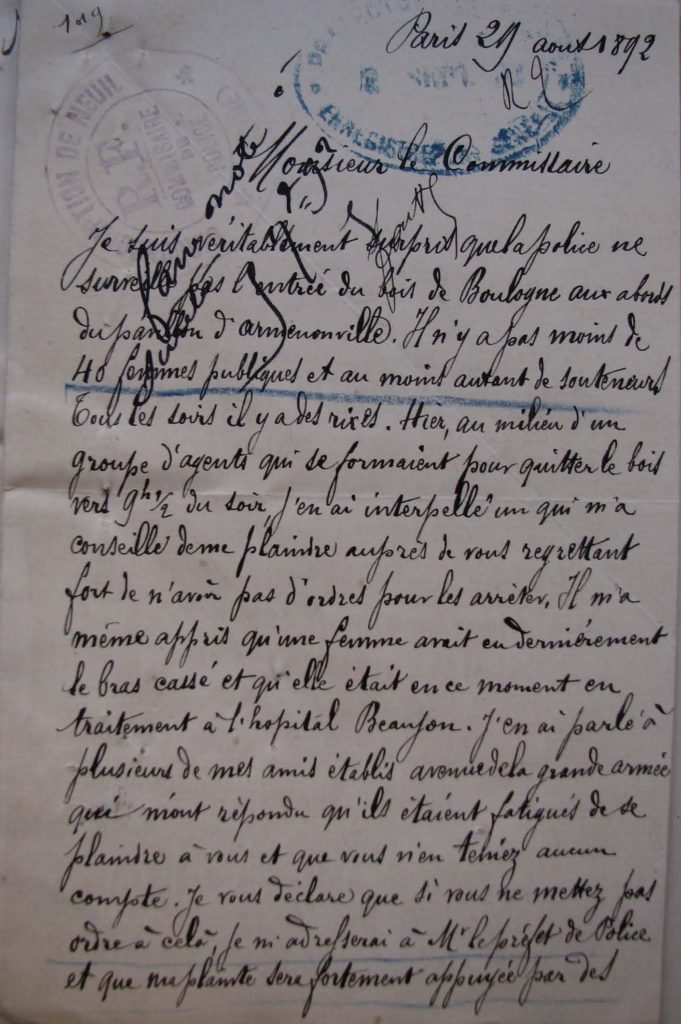

Calling the Police

About a week ago, just as the protests and uprisings against police brutality began in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, a woman named Amy Cooper called the police after being asked to put her dog on a leash by a Black birdwatcher named Christian Cooper (no relation) in Central Park. Prior to calling, Amy Cooper warned that she was “going to tell them [the police] there’s an African American man threatening my life.” As many others have noted, in doing so, Cooper deployed her white privilege to threaten the possibility of state violence in ways that resonated with the long history of white women pointing fingers at Black men who were then subjected to extrajudicial violence. The most famous case, of course, was the lynching of Emmett Till who was murdered in 1955 after a white woman named Carolyn Bryant claimed that he had whistled at her. Bryant recanted in 2017.

I started thinking about this moment again as I continue to work through Josephine Butler’s Government by Police (1879). Butler connects the growth of police power in both Continental Europe and in the United Kingdom to the growth of moral policing, especially around the development of regulated prostitution. For Butler, then, the police posed both a general danger to liberal society and a particular danger to women. Butler’s feminism — at first — was thus organized around protecting women from the police, not calling on them in women’s defense.

Continue reading “Calling the Police”Josephine Butler on the Police

I started drafting what I thought might be my first op-ed based on my current interests in Josephine Butler (1828-1906) and her campaigns against regulated prostitution in France. But as I was writing, I realized that some of what I was saying may be better kept for the article I’ve been hammering at for the better part of a year. At the same time, I still wanted to take a moment to lay out some of the things I’ve been thinking about regarding my own research’s connection to the current protests against police brutality.

Butler is most famous for her campaigns against the Contagious Diseases Acts in 1870s and 1880s Britain, as well as her participation in W.T. Stead’s ‘Maiden Tribute’ exposé and her later campaigns against regulated prostitution in the British colonies. Her interest in these issues remained rooted in her feminism, one inscribed within both the promises and problems of the time in which she lived. Her attention to the plight and vulnerability of working-class women and her pointed critique of the sexual double standard existed alongside her condescension toward the very women she sought to help and her commitment to English nationalism, imperialism, and white supremacy. Her campaign against regulated prostitution, however, was only one piece of a broader argument she levied against police authority more generally.

Continue reading “Josephine Butler on the Police”Some New Stuff

I had a couple items appear over the winter holidays. First, I reviewed Jeffrey Merrick’s Sodomites, Pederasts, and Tribades in Eighteenth-Century France, an invaluable source collection for those interested in the history of sexuality in eighteenth century France:

Merrick’s contribution is unique in its ambition. Sodomites, Pederasts, and Tribades in EighteenthCentury France forms one part of a broader reconceptualization of eighteenth-century sexual lives that explicitly invites readers to “track down, dig up, root out, and take in as much as we can about the operations and regulation of sexual desire and networks in eighteenth-century France and to locate the patterns and insights we extract from the sources in the context of the society that produced them and of larger issues in the history of sexuality” (p. 2). The give-and-take between Merrick, the documents, and readers thus produce new understandings of what the history of sexuality could mean to professional historians and students. As both a research intervention and a teaching tool, Sodomites, Pederasts, and Tribades accomplishes a rare feat. It simultaneously showcases the process and the results of archival research. It does so, however, without foreclosing the ways its readers will respond to and interpret the history it reveals.

Read the whole thing here.

Second, I was interviewed by Beth Mauldin of the New Books in History Podcast about Public City/Public Sex. I hate hearing my own voice, but I think it came out pretty well! Enjoy!

Book Publicity

I’ve been lucky to have been invited to talk about my recently published book in a few forums (Amazon link).

First, I was interviewed for 19 Cents, the blog of the Nineteenth-Century Studies Association.

I also discussed the book with Notches, a blog devoted to the History of Sexuality.

You can check out an excerpt of Public City/Public Sex in Lapham’s Quarterly.

New Syllabi

I was a bit behind updating my course syllabi, but new examples are now available.

Reading Tara Westover’s Educated as a Professor

I don’t often read memoirs (or non-fiction more generally) for pleasure, preferring to keep business and pleasure separate, but I had heard nothing but good — rapturous really — things about Tara Westover’s Educated and decided to check it out (of my amazing local library). The book vividly retells Westover’s life as a child growing up in an isolated family in Idaho, the daughter of an abusive father whose paranoia drives him to reject any interaction with the government, including, most importantly, public education. As we follow Westover’s path to college at Brigham Young University and then onward to Cambridge on a Gates Fellowship and then to a Ph.D., we witness in gross detail the mental and physical abuse that Westover suffered not simply before she “escaped” but as she worked to figure out just what escaping meant to her. Indeed, the book is particularly evocative and complex in the way it gets the reader into Westover’s head, underscoring her own doubts, struggles and, most powerfully and disturbingly, complicity in the cycles of abuse that so defined her family. In this respect, I can only compare it favorably with another memoir of overcoming struggle in order to achieve an education, Undocumented, which sometimes felt like it was effacing complexity in favor of narrative-pacing. Undocumented felt, for lack of a better term, teleological. Educated underscores how difficult is it to escape one’s past, how even as we are succeeding we may feel like we aren’t or don’t deserve to, and, most of all, that we sometimes are our worst enemies. Educated is often uncertain about its own conclusions, the memories it presents, and the finality of its story.

Obviously, the book has a great deal to say about Westover herself, as well as the social forces that created the conditions for the paranoia, mental illness, and misogyny that gave rise to her particular circumstances (in this respect, I highly recommend listening to the podcast Bundyville as a complementary story about the kind of Mormon fundamentalism that Westover’s father subscribed to). It also has a great deal to say about how one becomes educated in the first place and the complicated ways her education forces her to reevaluate her identity. Westover, it is worth noting, did not simply “choose” to go to school; she had to be pushed. Reading it on the cusp of a new school year, however, cannot help but reverse the analysis somewhat: to focus on some of the people around her, especially her teachers.

Continue reading “Reading Tara Westover’s Educated as a Professor”Pre-Order my Book!

I am very pleased to announce that my book Public City/Public Sex: Homosexuality, Prostitution, and Urban Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris, is now available for pre-order! You can buy it on Amazon, but you can get 20% off the paperback by ordering directly from Temple University Press with code T20P.

Strangers on a Plane

[Warning: Discussion of sexual abuse in this post]

Do not talk to me on an airplane. When I sit down, normally with headphones already on, book in hand, I am not inviting a conversation with a stranger. And yet, my most recent trip (a short hour and change flight, thankfully) these standard strategies utterly failed in the face of an older woman who just needed to chat. I could tell, 20-minutes in, that I was not escaping this so I settled into a rhythm of “uh huhs” that I figured I could keep up for the rest of the flight. The worst that would happen, I assumed, was that I lost an hour while providing some company to a lady who, at most, lacked the self-awareness necessary to realize that I just wanted to finish my novel. But what a chat it became.

It started innocuously enough. She told me about her life, her children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren. She was a retired teacher and school superintendent and a pastor. She told me about beginning teaching at 19, barely older than her students, and some of the problems and difficulties that entailed. She worked for 42 years before retiring. Things took a turn, however, when she began tell me why she doesn’t substitute teach any longer. She told me about an incident when she had to call a young kindergartner’s parents after the child had swore at her (“bitch, don’t touch me,” she claimed she said). Obviously not a good look for a five-year old, though who knows if that’s what was actually said. In any case, my airline companion proceeds to explain that she called in the students parents and it turns out that it was two dads. The child, who the teacher assumed was a girl, turned out to be a boy wearing girls’ clothes.